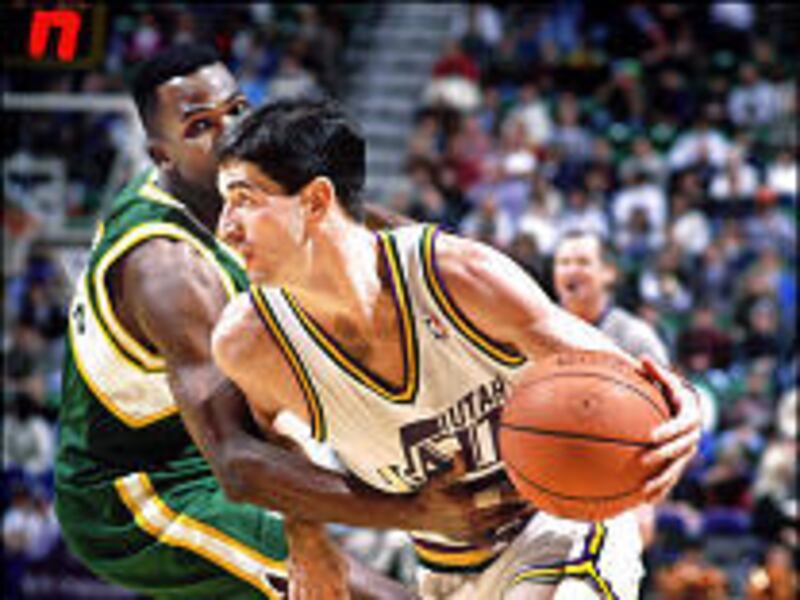

For 19 years, he performed on the most public of stages. More than 1,500 times, thousands watched him work. For nearly two decades, John Stockton played, and starred, in the NBA.

All the while, his biggest battle may not have been wins and losses. Instead, the fight to maintain his privacy was the one that really boiled Stockton's blood.

Because beyond the 3,265 steals, beyond the 15,806 assists, beyond the longevity of the game's purest of points, there is a person.

A shy man. Introspective. Perhaps even an introvert, some might suggest.

Now, more than 18 months after he shocked even some of those closest to him with an announcement of retirement, the point guard who spent his entire professional career with the Utah Jazz lets his guard down.

Just a bit.

Tonight, during a ceremony at halftime at the Jazz's game against the New Orleans Hornets, his No. 12 jersey will be hoisted in retirement to the rafters of the Delta Center, joining those assigned to former coach and general manager Frank Layden; the late, great showman Pistol Pete Maravich; scoring sensation Darrell Griffith; 7-foot-4 center Mark Eaton; and one of Stockton's closest friends from when the two were teammates, sharpshooter Jeff Hornacek.

Tonight, the 19-season career of the NBA's all-time leader in both assists and steals will be celebrated.

Last month — in the serenity of his hometown of Spokane, Wash., to which he and his wife, Nada, and their family of six children relocated very shortly after his playing days came to a close — Stockton spoke.

He did so not in snippets, not with that deer-in-the-headlights look he so often had when being interviewed, but instead in the most revealing of manners. He spoke freely, the burden of day-to-day scrutiny apparently having eased his intensity. He told, as only John Stockton could, the tale of how and why one of the game's greats decided to walk away.

And just how hard it was.

"That was a bad three days," Stockton said. "It just was ugly."

Even when he walked off the floor of Arco Arena in Sacramento for the final time on April 30,2003, Stockton did not know.

The Jazz had been eliminated from the first round of the NBA playoffs for the third time in three years, a far cry from the NBA Finals appearances — and subsequent back-to-back losses to Michael Jordan's Chicago Bulls — of 1997 and '98.

The Kings' crowd had offered a stirring goodbye ovation.

Yet even at the age of 41, the Gonzaga University product who performed with such certainty throughout his pro career just could not be sure.

"I didn't know it until I said it," he said. "That was very hard. In fact, I don't know anybody (knew). I discussed it with my wife, my kids, my parents, (longtime teammate and good friend) Karl (Malone). And, in my mind, I guess it was a process of working toward that. But, in theirs, I certainly didn't tell them."

When Stockton gathered a small group of somewhat unsuspecting reporters in the Jazz's locker room at the Delta Center for an informal end-of-the-season question-and-answer session, the bomb fell.

Malone — long over it now — was miffed the media had been officially told first, because even he wasn't sure what Stockton was planning.

"He's not the only one," Stockton said. "And yet, looking back, I don't know that I personally could have done it another way. So, I stand by the way, and how, I felt I had to do it, and how it happened. But I don't expect everybody to agree with me."

Retirement, in Stockton's mind, was a process.

It took time.

Time he has so much of, yet so little of, now.

In Spokane, Stockton's life is a blur.

With kids ranging from a toddler to those soon ready for college, how can it not be?

"There isn't anything typical," he said. "All I know is that when school ends, that's when the treadmill starts. I mean, swrhwwww. It's humming until bedtime — and I enjoy that part. I look forward to it."

That's why Stockton now follows the NBA only from a distance, catching little more than an occasional newspaper report or television highlight segment about the Jazz.

Even while 18-season-long teammate Malone was toiling last season for the Los Angeles Lakers, Stockton stayed away from the tube.

"I didn't see a lick," he said. "It wasn't an attempt to distance . . . or anything weird. I just couldn't do it.

"I only saw Karl take one shot in the whole season, and that was because at a restaurant we were at having dinner the Laker game was on. The kids pointed it out. I hadn't even noticed it. They said, 'Hey, Karl's playing.' So I looked back and up, and there he was shooting a shot."

Last season, his first out of the league, Stockton made it back to Utah for exactly one Jazz game. There was time for no more.

Again, that was part of no intentional plan. Rather, it was merely a nod to the reality of what his routine — or lack thereof — has become.

"It's busy," Stockton said. "Even people — and I hate to put it all on my kids, or make it sound like I'm whining, because I'm not — but I don't think people understand just 'the time.'

"I like to do things with my family. And if you like to do things with your family, there just isn't a lot of time in the day. I have two high school kids that are trying to play three sports. I have an eighth-grader right now who's trying to play three sports. My daughters, more than that each. And we have a baby that's 3 years old. Just the juggling of time is incredible.

"We're looking at two-hour windows. People ask us what we're doing, for example, tomorrow. 'Can you ask me tomorrow?' And it has to be flexible, or it doesn't work. So, you have things in line — but you also have to be flexible, which is interesting."

The schedule, Stockton said, simply did not allow him to return to Salt Lake City more than the single time he did.

"We have five kids all playing basketball," he said. "That doesn't offer a lot of time.

"To just find even a day to get back there was very hard. We have great friends we'd like to see. Obviously, it would be fun for the kids to come see that from a different perspective. And it just hasn't worked out."

Many of Stockton's days now that the playing has passed are filled with coaching.

Kids, that is, not in the NBA.

And they are not just his children, either.

"I learned, actually, from a guy in Salt Lake that it's very difficult to just coach 'your kids,' " he said. "They don't get anything out of it, and nobody else does. But if you're willing to coach 'people,' and your kids are in with it, then they both gain — and you feel better about it."

So does Stockton, who fills the void of competition that way now.

"I can appreciate how (Jazz coach) Jerry (Sloan) and these guys (Jazz assistant coaches) feel. Obviously, it's a different level. But you're still competing when you're coaching and helping people get better — whether they're even your team or not," he said. "If you can help a kid out, and he's playing for a team that plays against traditionally what's 'your team,' but he's doing well, you take a lot of satisfaction in that too."

Not everyone has the time to get so involved.

But Stockton does because pro athletes retire before the rest of us, and he is one among those who now has the financial wherewithal to spend more time than most with his family — time that once flew by as one season blended into another and another and another.

"I take it for the blessing it is — and I do realize that not everybody gets the opportunity," Stockton said. "So I guess you have to appreciate those things — and I do."

What Stockton did not appreciate when he played is when fans tried to cross the line between watching and idolizing.

On the road, he would often go out of his way to avoid crowds of autograph-seekers — sometimes even exiting hotels from a back entrance and walking the long way around the team bus so he could board without being seen.

Other times, he did what he felt was right.

Every day away from home, though, seemed to be a battle in the war with privacy maintenance.

"Jerry (Sloan) was great about letting me, or us, be basketball players," Stockton said. "It wasn't a prerequisite to be a celebrity, or a hero, or . . . a 'target.' "

Even today, Stockton can hear Sloan: "Just go play," the coach would say. "That's all I'm asking: Just go play, and be a good person."

That freedom loomed large on the list of reasons Stockton liked so much to play in Salt Lake — and probably would not have lasted nearly as long as he did if he had been traded to virtually any other NBA locale.

New Orleans or Orlando? No go. Boston or Philadelphia? Wouldn't work. New York? Forget about it.

"The beauty of Salt Lake, for the most part — and there are exceptions — is that people did mostly respect your space," Stockton said. "One of the beauties of playing there is that you could walk down the street, and even if people recognize you . . . for the most part, they give you your space."

The last question Stockton was asked as an NBA player was a simple one.

What will you miss most?

Stockton said he did not know, then turned and walked away, declining to elaborate, so as not to break down, not to cry, in public.

Now, he can answer the query without any tears.

"You miss your friends, and the environment that you're put in where you can be friends," Stockton said. "You know — the dinners on the road, when you go sit around with Karl (Malone) and Horny (Hornacek) and Adam (Keefe), and . . . you're talking about everything under the sun. You come back and you see the coaches in the lobby (and) shoot the breeze with them for a few minutes. Those types of things."

Over 19 years, road life became second nature for Stockton. The Jazz would take a trip, and he would leave the family behind. It's just the way it was.

Spokane was and is his real home, but it, too, was on the back burner.

Utah became a home away from home, a place where he could take his kids to work more and more often as the eldest got older and savor watching them grow as he did.

If one wasn't hiding in the box beneath Stockton's locker seat, another might have been out on the court knocking down long-distance jumpers.

"(Jazz owner) Larry (H. Miller) was so good about kids and the environment in the organization," Stockton said. "They shot around after games. I had kids that were buddies with Charles (Barkley). They had buddies on other teams — whether I liked the guys or not. There were some guys I had to go head-on-head with that they were shooting around with before the game, having a great ol' time.

"I'm sure they miss that. But that was going to change anyway."

Eventually, one day, Stockton had to retire.

He knew it. So did everyone else.

But as much as anyone, he earned the right for it to come on his timetable. No one else's.

The only question was when.

So many other sports stars, Jordan among them, have explored the answer in the public spotlight: retiring, then un-retiring and retiring yet again.

"I can't analyze what those guys went through," Stockton said. "I imagine there's a lot of similar thoughts each time, and once they get there, some guys might stop and say, 'Well, wait a minute. That was sure a lot of fun.'

"Maybe they had hopes (for) what the end would be, and it wasn't that and they had to come back. I don't know. But, for me, it's been all positive. Well, nothing's 'all' positive. But it's been positive."

That is because Stockton was so sure when he made the call.

No one else might have known for sure, but — with just the right amount of time — he did.

That is why he delivered the news like he did: with a boom, and no regrets.

"Because it was so hard to make the decision in the first place," he said. "I mean, I didn't wake up one morning. It was such a process, and finally, when the time came, it was it. I didn't enjoy it — quitting. But it had to be done."

Stockton calls is "quitting" not "retiring." Either way, he said, "I just knew that I enjoyed playing a lot, and for me to give that up it had to be time. And it's proved to be absolutely true."

Stockton's defensive quickness was deteriorating at the end, but his ability to run a basketball team was never questioned by those who watched him most.

What went first, then? The body or the mind?

"Neither," Stockton said. "I didn't feel like I was incapable of continuing to compete, mentally or physically."

It's just that he was ready.

On May 2, 2003, two days after the exit at Arco, last call came for the son of a Spokane tavern proprietor. He would step out of the spotlight and into the ultra-private realm retirement allows.

"You lay it all out there — whatever it is you have — and you walk home proud," Stockton said. "Those are lessons I learned growing up that paid dividends.

"I don't know," he added, with a pause. "It was just very clearly time."

Watch it on TV

John Stockton's jersey will be retired at halftime during tonight's Jazz/Hornets game at the Delta Center. TV coverage begins at 6:30 p.m. on KJZZ Channel 14 with a pregame live segment including Stockton. Game coverage begins at 7 p.m. KJZZ is broadcasting the entire halftime ceremony.

E-mail: tbuckley@desnews.com