MILFORD, Beaver County — Unless you like to tramp around in the backcountry, you may never have seen a charcoal kiln.

They are a part of a nearly forgotten industry that, in the words of one expert, came to be thought of "almost like a criminal activity."

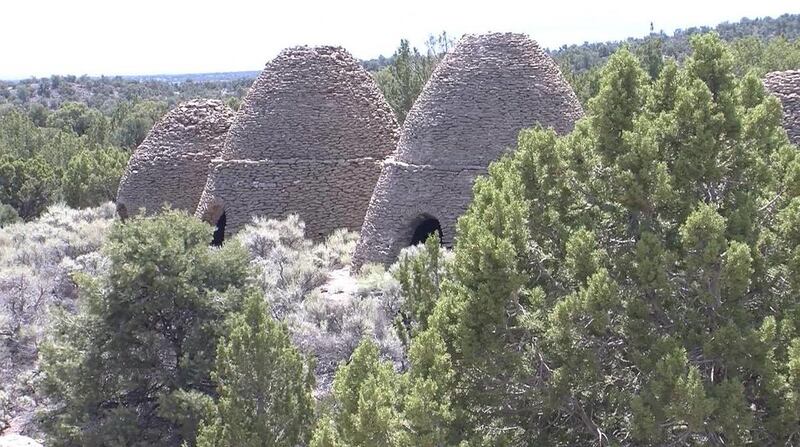

Retired U.S. Forest Service employee Doug Page recently drove through a pinyon-juniper forest, the kind used by charcoal kilns, on a road that's barely a road to a remote location in Beaver County. The site is called Seven Kilns and dates to about 1870.

"This is in really nice shape, really," Page said. “It’s part of American history that we’re fast forgetting.”

Page would like to see the kilns preserved.

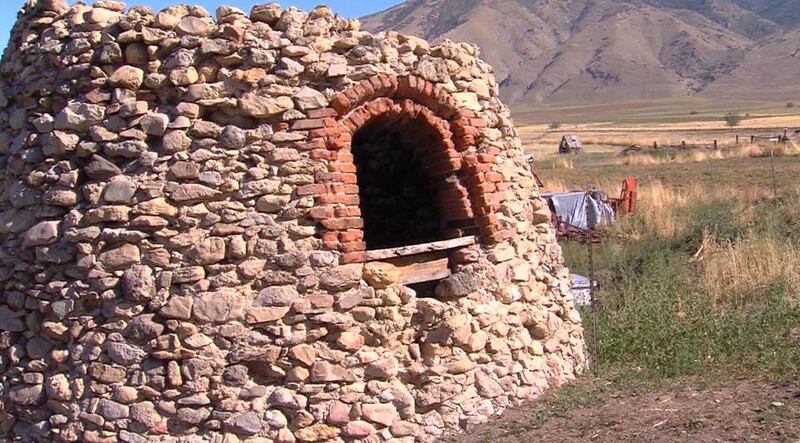

There’s another historic site, just outside Tooele, in Matt Peterson's backyard farm.

"Yeah, I'd like to see it kept and preserved the way it is,” Peterson said.

Peterson's kiln was built by the great-grandfather of Alice Dale, who is now the president of the Tooele County Historical Society.

“This is how they had to live it to survive,” Dale said. “It's pretty important. We learn from our history."

Bureau of Land Management archaeologist Nate Thomas says charcoal was critical to the mining industry. Kilns sometimes also made charcoal for homes and important buildings.

"Some of the charcoal within the Tooele area went to the Salt Lake Temple to heat the temple,” Thomas said.

Most kilns were at mine sites because charcoal was needed to smelt metals, a process discovered at least 6,000 years ago.

"Without metals, you wouldn't have had an Industrial Age, and without charcoal, you wouldn't have metals,” Page said.

People would cut down surrounding trees and burned them in the kilns, nearly smothered the fire to make it smolder very slowly.

"All the vents were sealed. The top was sealed, and it was left sealed for approximately a week to let it cool down so it didn't reignite,” explained Page.

The resulting charcoal was compact, tightly packed energy. Crucially, charcoal packed more punch than wood, burning hot enough to smelt metals.

"You need a hotter fire, roughly 2,000 degrees,” Page said.

In most cases, the kilns only lasted a few years. That's partly because they ran out of wood.

Kiln operators typically took out every sizeable tree within about a mile, according to Page.

"They basically clear-cut anything that could be used,” Page said. “A lot of times it was, 'Exploit an area, and move on.'"

"So in some parts of Utah, there was a mass deforestation,” Thomas said. “By the end, it was almost considered like a criminal activity."

Even today, some argue the economic tradeoffs were worth it.

"I think it was probably necessary to provide jobs for the people at that time,” Dale said.

"(It) made people a livelihood while they were here, so I think it was a good thing,” Peterson said.

But to Page, the lesson is still relevant.

"Take what you can, but never take everything if you want to keep a forest out there. Leave something there for the future,” he said.

Even those experts aren't sure how many kilns there were — or are. They've counted 41 just in a 30-mile radius near Seven Kilns, and they'd definitely like to preserve those that are still in good shape.

Email: hollehorst@deseretnews.com